Distal Hemorrhage Control: Can’t I just kneel on his groin?

Kneeling on the casualty’s groin for distal hemorrhage control

🕖 Reading Time, 5 minutes

When I was in the Special Forces Medical Sergeants course a very long time ago, I was taught a stopgap measure for significant lower extremity / groin bleeding was to “drop your knee into his groin” to stop bleeding while preparing your equipment for tourniquet placement or wound packing.

During my time as an SF medic, I did that a few times. Neither the casualties nor I found it to be a satisfying experience. Rarely would a casualty lie still as you placed a huge portion of your body weight on their groin/inguinal area. Instead, they would typically squirm and fight to get out from underneath your weight. If the casualty won’t tolerate the procedure, you don’t have a chance of achieving hemorrhage control distally.

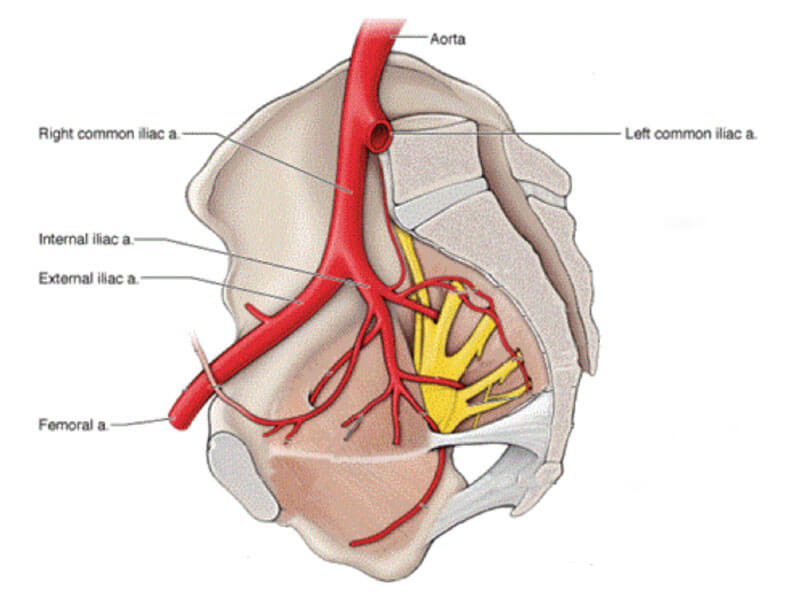

Many years later, in 2006 Dr. Blaivas published a, now much-quoted, ultrasound study1 looking at how much weight it took to compress your distal aorta and alternatively, the weight necessary to compress the inguinal arteries. He placed incrementally heavier dumbbells (on end) over a towel folded to be about knee sized, either over the distal aorta (upper abdomen, proximal to the umbilicus) or right lower quadrant of the abdomen. He then measured arterial flow on Doppler ultrasound at the common femoral artery.

No volunteer was able to tolerate enough weight to occlude flow through the distal iliac artery. One study participant tolerated a 100-pound dumbbell but still had flow.

Dr. Blaivas felt this disconnect in occlusion between the two locations was a byproduct of the distal aorta lying on top of the vertebral column, thus providing a firm backstop for aortic compression. , whereas the external iliac artery is posteriorly bordered by musculature making compression more difficult.

Since this study supported my own experience, I taught for years that kneeling on someone’s groin for distal hemorrhage control was primarily brought to you by the “good idea fairy.” An excellent idea that didn’t work well in the real world. Then came the era of inexpensive Doppler ultrasound and our ability to conduct informal evaluations and testing.

My first Doppler proven success with groin vasculature compression came about when testing an improvised technique for junctional hemorrhage 2involving placing a helmet in the casualty’s groin and tightening it in place with two CAT tourniquets. Surprisingly, it worked with either my Ops-Core helmet or the standard issue fire helmet of my Fire Department. Next, we showed a 500 ml disposable water bottle3 also worked very well to stop distal blood flow when placed on the groin crease. I rationalized this success with the Blaivas study and my own experience, presuming that the larger curvature of those items somehow facilitated vasculature compression that the human knee did not.

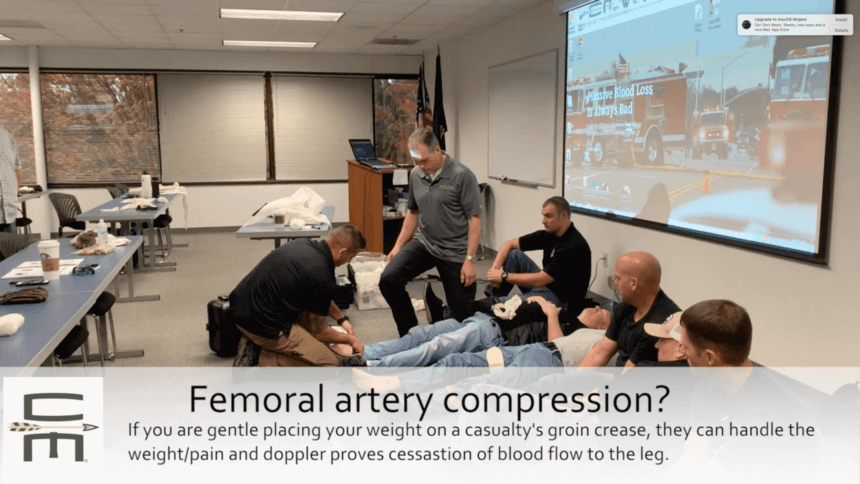

I then planned to kneel in groin creases at an in-person course to check if I could successfully compress the vasculature enough to occlude distal arterial flow and have the participant tolerate it.

With the Winter 2018 in-person Complete Tactical Casualty Care class, we used more than a dozen subjects and achieved 100% cessation of blood flow, thus success and tolerability as verified by Doppler. It was surprising how little pressure/body weight it actually took for compression. Further, when a knee was gently placed in the groin crease, blood flow stopped and the casualty tolerated the technique. Since that time, we’ve gone on to test this technique in in-person classes on over 200 students and achieved 100% success on Doppler.

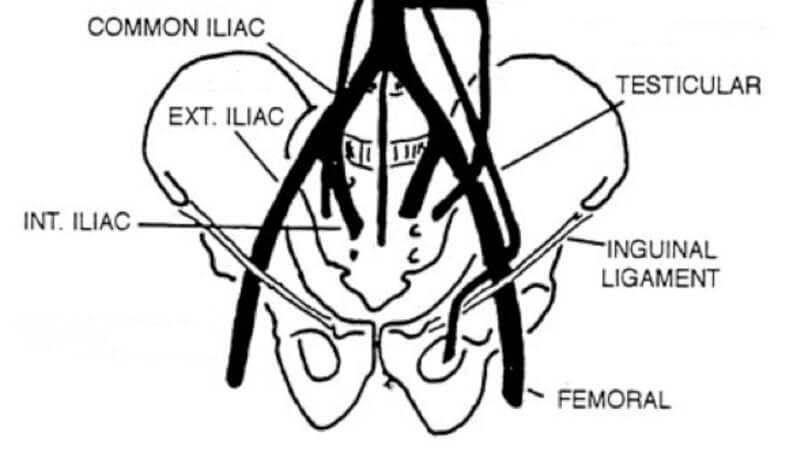

This caused a serious disconnect between my prior experience, the literature, and my new findings. Reviewing the Blaivas paper again, I noted his unsuccessful external iliac artery compression was performed by placing the weight in the volunteer’s right lower abdomen; not specifically his groin crease. Anatomically, the inguinal ligament is where the external iliac artery changes names and becomes the common femoral artery. It is the same piece of the vasculature, it just changes names once it leaves the abdomen.

The external iliac artery is buried deep in the pelvic brim until it surfaces and crosses underneath the inguinal ligament where it becomes the femoral artery. Once past the inguinal ligament, it is generally palpable as the femoral pulse.

In discussions with Dr. Blaivis, he chose the right lower abdomen to attempt iliac artery compression because it would generally be protected by armor in tactical settings and thus remain uninjured providing a place to control bleeding proximal, or above the wound.

What we really want to know is not, can kneeling on the casualties groin occlude his iliac blood flow, but rather whether we can occlude blood flow distal to the inguinal ligament.

We can’t occlude iliac blood flow with direct pressure because that vasculature is too deep and laying on top of muscle. Dr. Blaivis’s work proves that. Additionally, trying to pack that artery injury will also generally be unsuccessful because it is an intraabdominal wound in a large pelvic bowl. Wounds above the inguinal crease are in the torso and generally not packable without surgical exposure.

Putting on personal protection and getting a tourniquet out of your aid bag can seem like it takes forever when you are watching a casualty bleed. However, placing your knee gently in the casualties groin, below the inguinal ligament/groin crease of his trousers, works very well to compress distal flow through his common femoral artery as evidenced by the twelve students we tested it on in class.

SUMMARY: Putting your knee in a casualty’s groin can eliminate common femoral artery blood flow. The key is to place your knee gently in the groin crease, putting too much body weight into your knee will be painful to the casualty, and they will not remain underneath it.

References:

1 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17334183Blaivas M, Control of hemorrhage in critical femoral or inguinal penetrating wounds—an ultrasound evaluation. Prehosp Disaster Med 2006 Nov-Dec; 21(c):379-82

2 See, Improvised Junctional Tourniquet video at the bottom of the list