Is the Dial-A-Flow the most operationally useful way to manage IV infusions in a low-resource or austere setting?

- Posted by Mike Shertz MD/18D

- Categories (C) Circulation, Travel Medicine

BLUF: The Dial-A-Flow IV regulating device is a cheap, lightweight, and easy option for administering IV infusions when traditional IV pumps aren’t available. Although it’s accuracy to deliver the exact volume of IV fluid desired can be + / - 20%, it is faster than traditional IV drip chamber calculations and no less accurate at flow rates between 10 to 250 ml an hour. Like all IV infusions, periodically checking and adjusting the flow rate will be required.

🕖 Reading Time, 7 minutes

IV infusions in high resource environments

While assisting with a class for clinicians who might be called upon to manage medical patients well beyond ideal timelines for medical evacuation, the topic of IV infusions for sepsis and cardiogenic shock was discussed. In profound hypotension from either shock state, not responsive to IV fluid administration, an IV infusion of norepinephrine is the vasopressor of choice. The medication increases blood pressure in both conditions by increasing peripheral vascular resistance. Some patients require these infusions continuously for hours to days.

In high-resource hospitals, the ED and intensive care units run the infusions on IV pumps. However, in low-resource or austere environments, the expense, weight, cube, and requirement for batteries or electricity frequently render IV infusion pumps a non-viable option.

IV Drip Calculations

Traditionally, before the advent of IV pumps, nurses calculated drip rates based on the dose of the medication used, its concentration, and the number of drips per ml of the specific IV tubing used, before adjusting the roller clamp on the IV tubing to achieve the correct number of “drips” per minute in the drip chamber.

As a clinician in a high-resource hospital, I order the desired vasopressor dose in the computer, the pharmacy mixes the medication in an IV bag, and the nurse places the IV Infusion in a preprogrammed pump which delivers the dose I ordered. No one does drip calculations anymore.

Asking medical providers who never do drip calculations to tabulate and execute a precise IV infusion dose correctly will be a high cognitive load and likely not very accurate for their patients.

Solution for IV administration in austere or low resource environments

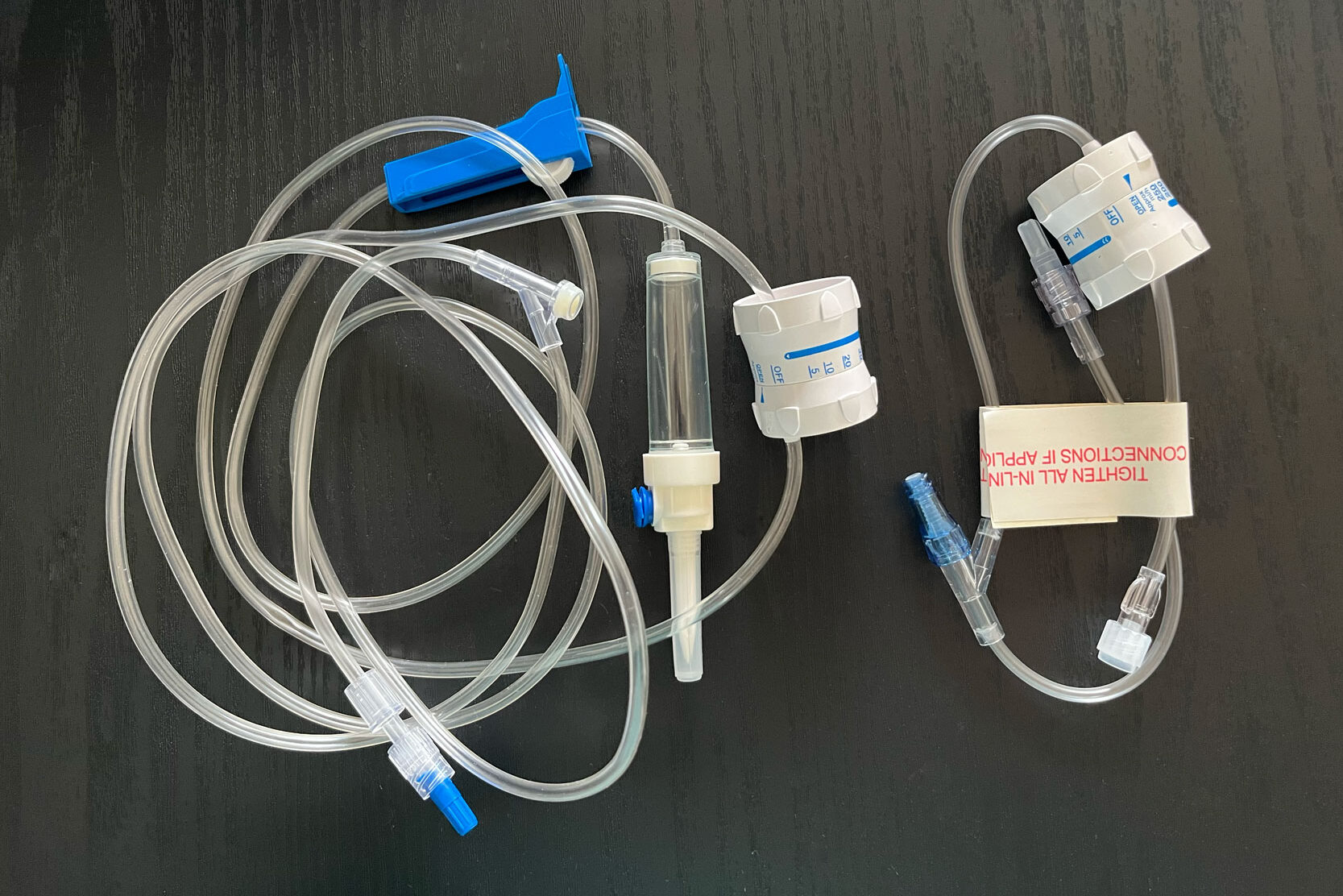

Enter the Dial-A-Flow IV device. This simple dial-type flow limiting device allows the adjustment of IV infusions between about 10 to 250 ml per hour. With its low cost, (generally only a few US dollars), and minimal weight/cube (appx 9 grams), it seems the perfect operational way to administer IV infusions when traditional IV pumps aren’t available.

Logically, the next question is how accurate is this 1970’s era device? Traditional IV infusion pumps have an error rate of delivering 10% plus or minus the programmed IV fluid volume.1 Traditional IV drip calculations have inherent issues with roller creep or “cold flow.” Cold flow occurs when the soft plastic of the IV tubing changes over the first hour of the IV infusion under the IV tubing roller clamp. These changes typically decrease IV flow by 38% or more. Modern IV tubing/roller clamps minimize but do not eliminate this effect.2

Per the manufacturer’s specifications, the Dial-A-Flow device delivers the “dialed” flow rates from off to 5 to 250 ml per minute when the IV bag is flowing with the IV tubing roller clamp “wide open,” and the IV bag is hung 30 inches above the IV site.

In a study of 360 experimental infusion “runs” with the device, using 12 different flow rates, the fluid volume delivered was incorrect compared to what was desired by a volume of +/- 20%. This result became particularly inaccurate at flow rates below 10 ml/hr, where the error volume was + /- 68%. Although based on these results, the authors felt the Dial-A-Flow device was no more accurate than traditional IV drip chamber calculation, one can also interpret this data as showing the device is as accurate as tedious IV drip chamber calculations and faster to set.3 In a separate study using 60 experimental runs of the device across six flow rates and with the IV bag either 30 or 40 inches above the IV site, the delivered IV fluid was consistently under what was “set” on the dial by 11% at 30 inches and over what was expected by 10% with the IV bag elevated above the manufacture’s height recommendations.4

Studied in an aeromedical transport helicopter with the IV bag on a hook in the aircraft (36 inches above the IV site) and a set flow rate of 30 ml/hr, after 18 runs, the delivered IV fluid was an average of 23% (37 ml) above expected. The authors concluded that “when translated into use with common drug infusions, this error is probably within acceptable limits.”5

On 20 runs at set flow rates of either 30 or 100 ml / hr with the IV bag 30 inches elevation, the device underdelivered the desired volume of IV fluid by about 25%.2 Here, the authors decided the device wasn’t accurate enough for clinical use.

How do you reconcile these two opinions? The Dial-A-Flow device generally delivers about + / – 20% of the expected IV fluid. Knowing that, all IV infusions need to be periodically spot-checked every hour or so, and the IV volume delivered (missing from the hung IV bag) noted. You can then make adjustments to the dialed flow rate to compensate. Ultimately, all IV infusions must be watched to avoid “runaway drips” where an unintended fluid volume is administered.

The device was studied as a means to deliver set flow rates of total parenteral nutrition (TPN), but a high breakage and infection rate was found clinically. Similar issues with IV fluid administration have not been reported. TPN is a known substantial infection risk as you are putting “IV food” into the patient, and that liquid is prime for bacterial growth.6

Studied in volunteers who had IVs placed and set flow rates on the Dial-A-Flow, frequent position changes from lying to sitting, standing, and walking made it difficult for the device to maintain a set flow rate.7 However, none of that is surprising; that is asking a bit much from a gravity-fed IV. Standard drip chamber calculations would have the same altered flow issues.

In the most recent study of two different manufacturers of a Dial-A-Flow device, using various IV bag heights in an ambulance, the same height effects were again seen. If the bag is higher than 30 inches, the delivered volume is more. A lower bag under delivers. This result has been noted before. These authors felt that since the devices were less accurate than a traditional IV infusion pump, they shouldn’t be used by prehospital providers. We agree, that is, if you have a pump. If you don’t, this still seems a very operationally viable option.1

Although available in a stand-alone IV extension tubing or inline in an IV administration set, we recommend the extension tubing version. Since its maximum flow rate is 250 ml an hour, using a version built into an IV administration set will prevent you from having the option to bolus IV fluids at rates above 250 ml an hour, should they be necessary, which is frequently the case in septic/cardiogenic shock. Alternatively, when used in the extension tubing version, if faster flow rates are needed, the Dial A Flow could simply be removed from the IV admin set, and the IV fluid run as “wide open” as one desires.

NOTES:

1Loner C, Acquisto NM, Lenhardt H, Sensenbach B, Purick J, Jones CMC, Cushman JT. Accuracy of Intravenous Infusion Flow Regulators in the Prehospital Environment. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2018 Sep-Oct;22(5):645-649. doi: 10.1080/10903127.2018.1436208.

2Horrow JC, Jaffe JR, Rosenberg H. A laboratory evaluation of resistive intravenous flow regulators. Anesth Analg. 1987 Jul;66(7):660-5. PMID: 2955718.

3Rithalia SV, Rozkovec A. Evaluation of a simple device for regulating intravenous infusions. Intensive Care Med. 1979 Mar;5(1):41-3. doi: 10.1007/BF01739002. PMID: 438425.

4Lambert JB, Buchanan N. Accuracy and reproducibility of Dial-A-Flo infusion meters. Med J Aust. 1982 Feb 6;1(3):106. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1982.tb132186.x. PMID: 7132847.

5Classon R. Dial-a-flo: How accurate are manual IV rate control devices during helicopter transport?, AeroMedical Journal, 1987, Volume 2, Issue 3, Pages 14-1.

6Mitchell A, Kettlewell M. Dial-a-Flo: a warning. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1982 Jan;64(1):59. PMID: 19310782; PMCID: PMC2493997.

7Carleton BC, Cipolle RJ, Larson SD, Canafax DM. Method for evaluating drip-rate accuracy of intravenous flow-regulating devices. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1991 Nov;48(11):2422-6. PMID: 1746576.

As with all Crisis Medicine posts, this information is not sponsored, and we receive no compensation from any vendor regarding this review of the medical literature. It is provided as a matter of interest to our students. Please see our Disclosures for any questions (BLUF: We have none).

Dr. Mike Shertz is the Owner and Lead Instructor at Crisis Medicine. Dr. Shertz is a dual-boarded Emergency Medicine and EMS physician, having spent over 30 years gaining the experience and insight to create and provide his comprehensive, science-informed, training to better prepare everyday citizens, law enforcement, EMS, and the military to manage casualties and wounded in high-risk environments. Drawing on his prior experience as an Army Special Forces medic (18D), two decades as an armed, embedded tactical medic on a regional SWAT team, and as a Fire Service and EMS medical director.

Using a combination of current and historical events, Dr. Shertz’s lectures include relevant, illustrative photos, as well as hands-on demonstrations to demystify the how, why, when to use each emergency medical procedure you need to become a Force Multiplier for Good.