Distracting but not life-threatening: Managing abdominal eviscerations

- Posted by Mike Shertz MD/18D

- Categories More

🕖 Reading Time, 5 minutes

A recent TCCC update focused on the management of abdominal eviscerations. The primary focus of this update was to adjust management of the eviscerated bowel in the hopes that the bowel itself will remain viable, not dry out, dieback from decreased blood flow to the injured portion, or be an unnecessary source of infection.

Traditionally, abdominal wounds represent about 20% of injuries presenting to hospitals in times of war. In historical conflicts, abdominal wounds were generally felt to be fatal if from bayonets. The mortality decreased during WWI as more casualties were taken for exploratory abdominal surgery. Still, at the time, the death rate was 55 – 77%. Prior to this time, any penetrating abdominal wound was triaged as expectant.1 It has gradually decreased since WWI, and during Vietnam the mortality was between 4 – 12%.2

During the recent Global War on Terror, abdominal wounds represented 9.4% of all wounds with 81% caused by explosions and 17% secondary to gunshot wounds.3 However, there is no current data on how frequently eviscerations accompany those abdominal wounds or are a cause of death in modern combat.

There are no scientific studies evaluating the prehospital management of abdominal eviscerations.

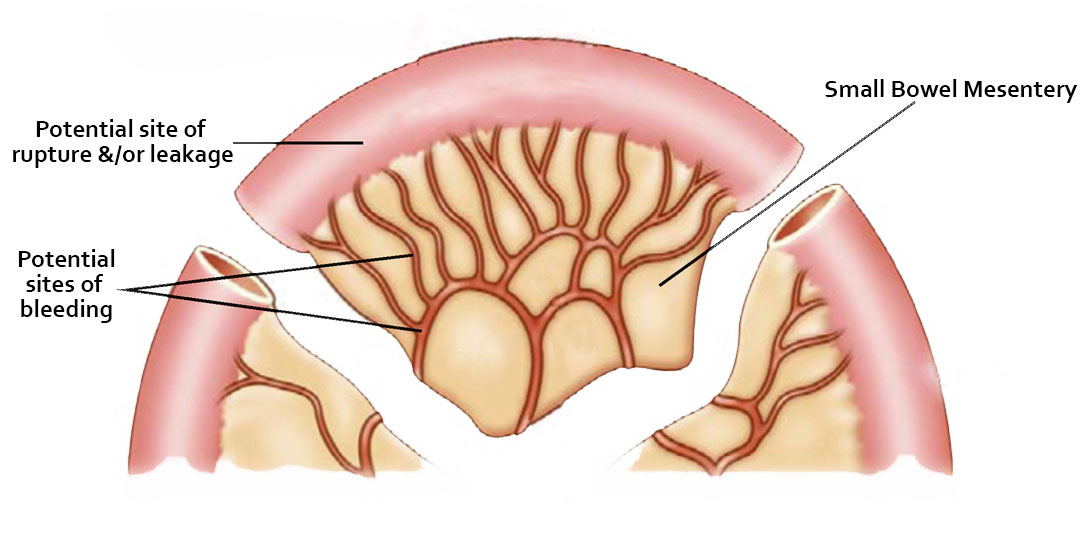

All recommendations constitute “expert opinion” only.

With that being said, the TCCC committee would like any site of bleeding on the eviscerated bowel controlled. Often direct pressure to the exact point of bleeding is possible as the bowel is exposed and accessible, by definition, with an evisceration. Hemostatic or regular gauze can be used. Rising the bowel with clean water or saline to remove obvious debris is recommended. To decrease the likelihood the exposed bowel will dry out, it is suggested the bowel be covered with moistened gauze and placed in a waterproof bag. Clear material is preferred for the bag, so any recurrent bleeding can easily be seen. Plastic packing material from bandages or IV bags could be used. Co-TCCC suggests taping or using a chest seal to adhere the plastic bag to the abdominal wall to secure it in place.

In a military or tactical setting with a possible delay in evacuation, a quick attempt at reducing the eviscerated bowel is reasonable. The committee suggests not spending more than 60 seconds trying to do this. If the bowel can’t be easily reduced, then cover and secure it as above.

If there is a rupture or leakage of the bowel contents, no attempt should be made to reduce the evisceration as that would just spill bowel contents into the abdomen, all but ensuring significant intra-abdominal infection. Similarly, if any associated bowel bleeding can’t be controlled, that too is a contraindication to reduction.4

Ultimately, abdominal eviscerations are dramatic appearing wounds but not immediately life-threatening. All lifesaving interventions including external hemorrhage control, needle decompression of suspected tension pneumothorax, relieving airway occlusion, etc. should be completed before turning your attention to the evisceration.

Placing the eviscerated bowel in some clear plastic bag or wrap with moistened gauze makes sense as it will decrease the likelihood of them drying out. If you can get that bag to stay in place with tape or a chest seal used as tape that too seems reasonable. If not, our traditional “gut taco” can still be used to secure the bag/bowel combination around the casualty’s waist, but bowel bleeding will be less obvious.

→Photo at top from a 14-year-old boy who sustained a penetrating injury to his abdominal wall after impacting the handlebars of his bike. Note the bowel perforation at approximately 7 o’clock on the bowel. This should not be reduced, as it will spill bowel contents into his abdomen. 5

Notes:

1 Wilke HT, et al. Massive Traumatic Evisceration, Am J Sur 1943;62(2):282-285

2 Hardaway RM 3rd. Viet Nam wound analysis. J Trauma. 1978 Sep;18(9):635-43

3 Owens BD, Kragh JF Jr, Wenke JC, Macaitis J, Wade CE, Holcomb JB. Combat wounds in operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom. J Trauma. 2008 Feb;64(2):295-9

4 Riesberg JC, Gurney JM, Morgan M, Northern DM, Onifer DJ, Gephart WJ, Remley MA, Eickhoff E, Miller C, Eastridge BJ, Montgomery HR, Butler FK Jr, Drew B. The Management of Abdominal Evisceration in Tactical Combat Casualty Care: TCCC Guideline Change 20-02. J Spec Oper Med. 2021 Winter;21(4):138-142

5 Ulusoy E, Serpen B. Unexpected Complication from Blunt Trauma: Evisceration. J Pediatr Emerg Intensive Care Med 2018;5:129-131

Dr. Mike Shertz is the Owner and Lead Instructor at Crisis Medicine. Dr. Shertz is a dual-boarded Emergency Medicine and EMS physician, having spent over 30 years gaining the experience and insight to create and provide his comprehensive, science-informed, training to better prepare everyday citizens, law enforcement, EMS, and the military to manage casualties and wounded in high-risk environments. Drawing on his prior experience as an Army Special Forces medic (18D), two decades as an armed, embedded tactical medic on a regional SWAT team, and as a Fire Service and EMS medical director.

Using a combination of current and historical events, Dr. Shertz’s lectures include relevant, illustrative photos, as well as hands-on demonstrations to demystify the how, why, when to use each emergency medical procedure you need to become a Force Multiplier for Good.