Use a Foley Catheter to stop massive junctional hemorrhage in narrow-track wounds

- Posted by Mike Shertz MD/18D

- Categories (M) Massive Hemorrhage, Equipment

🕖 Reading Time, 15 minutes

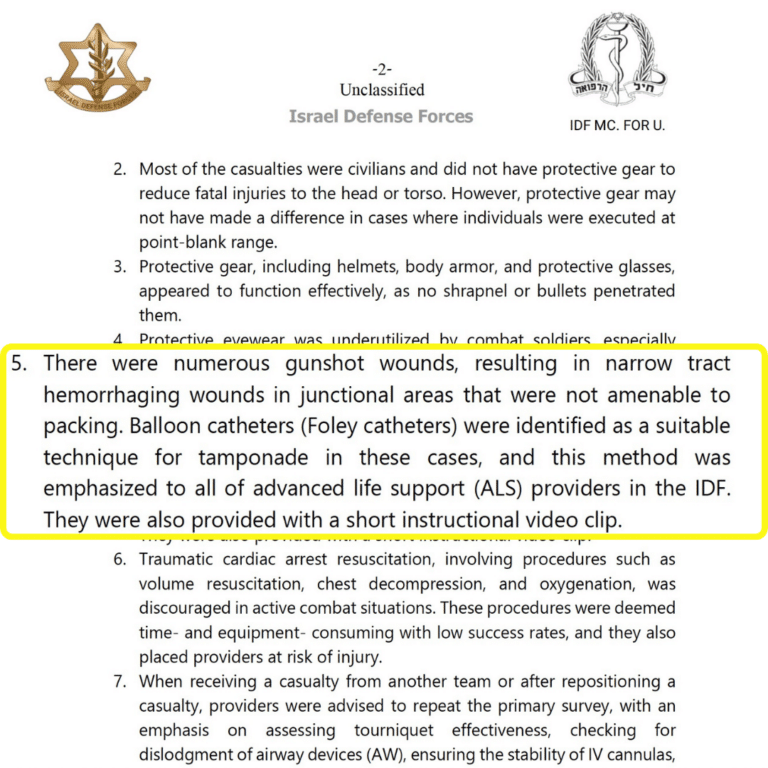

A recent IDF Medical Corps preliminary review of Israeli casualties from the Hamas attack on 7 OCT 2023 noted numerous gunshot wounds to junctional areas that were “narrow-tracked and not amenable to wound packing.” Based on their review, they determined urinary catheters used for balloon occlusion were a “suitable technique” to stop massive hemorrhage and are encouraging expanded use.

We have been teaching this technique as part of our online Advanced and Complete Tactical Casualty Care series since 2017. The entire video presentation and skill demonstration is available online at the crisis-medicine.com website for free (and now below).

BLUF: Junctional wounds are those wounds of the neck, axilla (armpit), and groin, not amenable to tourniquet application but are frequent sources of massive hemorrhage.

There are many different ways to manage these wounds, one technique uses a Foley Catheter (designed for urine drainage) to tamponade bleeding. Though best studied in neck wounds, it has been used throughout the torso. Included here is a literature update on the technique and teaching package from our Advanced / Complete TC2 online courses.

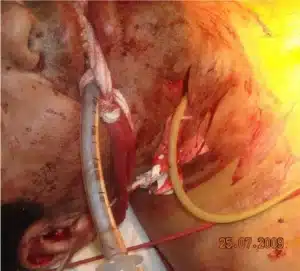

First, a foley catheter is inserted to the point of bleeding. Next, using a syringe filled with saline, the balloon is then inflated and the inflation of the balloon within the wound puts pressure directly on the bleeding vasculature. Once the balloon is inflated and bleeding is stopped, the catheter must be tied off to avoid leakage and a lessening of the direct pressure on the wound.

Placement of a urinary or “Foley” catheter into a bleeding wound to provide direct pressure to the point of bleeding has a long history of use. The first mention of using a balloon-type catheter was in 1906 when one was placed into a profusely bleeding liver injury from a .44 caliber pistol gunshot wound.1

Although utilized by trauma services throughout the world, most published medical literature on the technique involves specifically penetrating neck wounds with ongoing bleeding. This technique has been extensively utilized and studied in South Africa, which is responsible for most of the published medical literature. There, in bleeding neck wounds (139 patients) the most common mechanism of injury was stabbings at 91%, and gunshot wounds made up the remainder. 2

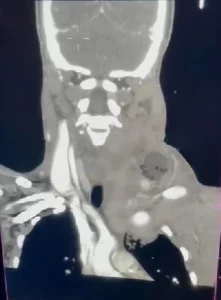

Placement of an 18 to 20 French urinary catheter into a bleeding neck wound to the point of bleeding, then inflating with sterile water/saline until the bleeding stops or resistance to additional inflation is felt, is 92% effective in controlling bleeding across multiple studies. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6

Finally, to help the catheter exert pressure on the point of bleeding and not extrude itself from the wound, the overlying skin should be sutured or stapled closed. A more temporary technique is to use a mosquito hemostat to clamp the catheter against the skin, after the catheter is pulled tight, and then taping the hemostat against the skin, anchoring it in place. Finally, if the catheter was sutured or stapled in place, the catheter itself needs to be tied in a knot to prevent blood traveling up through the internal lumen of the catheter. Another advantage of clamping is that it eliminates this step.

This technique was also studied in a military hospital with 11 neck wound casualties from gunshot and grenade blasts, all secondary to counter-insurgency operations3, as well as a far forward aide station in Afghanistan where the overwhelming majority mechanism of injury for their neck wounds was IED and gunshot.5

The entire video presentation and skill demonstration of using a foley catheter for wound packing from Crisis Medicine’s Advanced and Complete Tactical Casualty Care classes.

The technique was compared to wound packing with hemostatic gauze, specifically Combat Gauze. Though the ultimate survival rate was similar between the two treatment groups (95% Foley catheter vs 89% CB), those packed with hemostatic gauze had more re-bleeding (29% vs. 7.5%) after initial hemorrhage control.

While best studied in bleeding neck wounds, the technique has been used in other anatomical areas. One common use in South Africa is for bleeding wounds in the supraclavicular area, i.e., above the collarbone. Subclavian artery or vein injuries can be difficult to manage prehospital. In that location, the catheter is inserted per usual and then pulled upward against the first rib/clavicle/collarbone and secured in place. Unlike most gauze packing techniques that have to be used in a wound pocket (packing gauze firmly in the wound generates pressure on the point of bleeding, something that can’t happen without a bottom to the wound), this catheter technique can be utilized even if the wound cavity itself isn’t contained, i.e., if the underlying lung is also collapsed.2

This technique has also been used in 29 inner-city torso trauma patients in South America, all with active bleeding from their wounds: 11 were injured by gunshot and 18 stabbed.7 There is another case series involving 44 torso uses. 8

Often overlooked but a reasonably researched technique, urinary catheter balloon tamponade of particularly narrow track wounds is a viable prehospital technique requiring little medical equipment. If you have a surgical airway kit, you already have a mosquito hemostat. If you have IV supplies, you have saline for balloon inflation. All you need to add is the urinary catheter. A small surgical skin stapler is also low weight and cube, and makes anchoring the catheter easier.

Many of the South African trauma service protocols leave the catheter, inflated, and in place for 24 hours2 or 48 hours.9 At that time they deflate it and if there is no ongoing bleeding it is removed and the patient never formally undergoes surgery, even with some minor arterial injuries identified on CT angiogram of the neck.2 From the standpoint of prolonger casualty / field care, this could be very beneficial.

References

1 Schroeder WE. The progress of liver hemostasis—reports of cases (resection, sutures, etc). Surg Gynecol Obstet1906;2:52–61.

2 Kong V, Ko J, Cheung C, Lee B, Leow P, Thirayan V, Bruce J, Laing G, Khashram M, Clarke D. Foley Catheter Balloon Tamponade for Actively Bleeding Wounds Following Penetrating Neck Injury is an Effective Technique for Controlling Non-Compressible Junctional External Haemorrhage. World J Surg. 2022 May;46(5):1067-1075. doi: 10.1007/s00268-022-06474-4. Epub 2022 Feb 24. PMID: 35211783.

3 Jose A, Managmeent of Life-Threateing Hemorrhage from Maxillofacial Firearm Injuries Using Foley Catheter Balloon Tamponade, Cranimaxofac 2019; 12:301-304.

4 Scriba M, McPherson D, Edu S, Nicol A, Navsaria P. An Update on Foley Catheter Balloon Tamponade for Penetrating Neck Injuries. World J Surg. 2020 Aug;44(8):2647-2655. doi: 10.1007/s00268-020-05497-z. PMID: 32246186.

5 Weppner J. Improved mortality from penetrating neck and maxillofacial trauma using Foley catheter balloon tamponade in combat. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013 Aug;75(2):220-4. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3182930fd8. PMID: 23823611.

6 Navsaria P, Thoma M, Nicol A. Foley catheter balloon tamponade for life-threatening hemorrhage in penetrating neck trauma. World J Surg. 2006 Jul;30(7):1265-8. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-0538-3. PMID: 16830215.

7 Himmler A, Maria Calzetta IL, Potes A, Puyana JC, Barillaro GF. The Use of a Urinary Balloon Catheter to Control Hemorrhage From Penetrating Torso Trauma: A Single-Center Experience at a Major Inner-City Hospital Trauma Center. Am Surg. 2021 Apr;87(4):543-548. doi: 10.1177/0003134820949997. Epub 2020 Oct 28. PMID: 33111566.

8 Ball CG, Wyrzykowski AD, Nicholas JM, Rozycki GS, Feliciano DV. A decade’s experience with balloon catheter tamponade for the emergency control of hemorrhage. J Trauma. 2011 Feb;70(2):330-3. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318203285c. PMID: 21307730.

9 Madsen AS, The Selective Non-operative Management of Penetrating Cervical Venous Truma is Safe and Effective, World J Surg (2018) 42:3202-3209.

Dr. Mike Shertz is the Owner and Lead Instructor at Crisis Medicine. Dr. Shertz is a dual-boarded Emergency Medicine and EMS physician, having spent over 30 years gaining the experience and insight to create and provide his comprehensive, science-informed, training to better prepare everyday citizens, law enforcement, EMS, and the military to manage casualties and wounded in high-risk environments. Drawing on his prior experience as an Army Special Forces medic (18D), two decades as an armed, embedded tactical medic on a regional SWAT team, and as a Fire Service and EMS medical director.

Using a combination of current and historical events, Dr. Shertz’s lectures include relevant, illustrative photos, as well as hands-on demonstrations to demystify the how, why, when to use each emergency medical procedure you need to become a Force Multiplier for Good.